|

...And here we are again, it's the weekend. Can't wait to sit back and relax after a very packed week. Honestly, the days seem to be zooming in incredible speed and I can't believe this weekend marks the end of the first month of 2015! It seems only yesterday I sat writing my 'new year resolutions' and 29 days later? Well, February is still technically a month at the beginning of the year isn't it? So what's the rush I'm thinking! It's always better to take it slow and come up with a solid plan and that's what I'm doing. Seriously! ;) 'Where oh where does the time fly?' was and continues to be a very regurgitated question by many a senior, i.e old, members of my family. Before I got to the age I am at now, my younger siblings, cousins and I would always roll our eyes when we heard this and file such a question, among many others, under 'Things Old People Say & Never Will We'. Lately, more often than is to my liking, I catch myself saying things that I vowed I'd never let pass my lips. I have also come to the horrifying conclusion that soon 'Mr. Fabulous Junior' will be filing my words under the same title or even creating one which reads like 'Old-yet-in-denial of her age & thus embarrassing things my mother says & I shall never say'. However, as I get wiser (one can only hope), I shall embrace my idiosyncrasies and whenever Junior complains I shall inwardly be 'mwahaha-ing' knowing he will one day be in my place. Anyway, this week has been great in catching up with friends that I don't normally get a chance to properly sit down with for a chat because of their busy lives. But my gorgeous friend Ambreen and I met at 'Nathalie's Cafe' in Abu Dhabi and had a beautiful chat over Pasta and Chicken bake (me) and a Chicken Quesadilla (Ambreen). The chat led to books (of course) and here are two that she really enjoyed and highly recommends. Enjoy the weekend & see you on Sunday!

0 Comments

Author Helen McDonald has won the Costa Book of the Year Award 2014 for her book, 'H is for Hawk' which is a book about the author's personal account training a goshawk as a way of dealing with the loss of her father. The £30,000 prize aims to honour outstanding books by authors based in the UK and Ireland and was previously called the Whitbread award. 'H is for Hawk' is the sixth biography to take the overall prize and the first in 10 years. About the Book: (from Random House) In real life, goshawks resemble sparrowhawks the way leopards resemble housecats. Bigger, yes. But bulkier, bloodier, deadlier, scarier, and much, much harder to see. Birds of deep woodland, not gardens, they’re the birdwatchers’ dark grail.’ As a child Helen Macdonald was determined to become a falconer. She learned the arcane terminology and read all the classic books, including T. H. White’s tortured masterpiece, The Goshawk, which describes White’s struggle to train a hawk as a spiritual contest. When her father dies and she is knocked sideways by grief, she becomes obsessed with the idea of training her own goshawk. She buys Mabel for £800 on a Scottish quayside and takes her home to Cambridge. Then she fills the freezer with hawk food and unplugs the phone, ready to embark on the long, strange business of trying to train this wildest of animals. ‘To train a hawk you must watch it like a hawk, and so gain the ability to predict what it will do next. Eventually you don’t see the hawk’s body language at all. You seem to feel what it feels. The hawk’s apprehension becomes your own. As the days passed and I put myself in the hawk’s wild mind to tame her, my humanity was burning away.’ Destined to be a classic of nature writing, H is for Hawk is a record of a spiritual journey - an unflinchingly honest account of Macdonald's struggle with grief during the difficult process of the hawk's taming and her own untaming. At the same time, it's a kaleidoscopic biography of the brilliant and troubled novelist T. H. White, best known for The Once and Future King. It's a book about memory, nature and nation, and how it might be possible to try to reconcile death with life and love. For more on this story and the reaction of Jane McDonald on her win, click HERE.

When/Where: Tuesday, January 27, 2015 | 6:30-8:00pm | NYUAD Saadiyat Campus, Conference Center, Open to the Public

The Event: Published between 1906 and 1930, Molla Nasreddin was a legendary Azerbaijani political satire read by an audience that stretched from Morocco to India. Arguably one of the most important periodicals of the Muslim world in the 20th century, the weekly addressed issues such as gender equality, education, colonialism, and Islam’s integration of modernity – all of which remain as relevant today as when the magazine was first published a century ago. Speaker: The lecture will be given by Payam Sharifi Artist and Essayist, Co-Founder of Slavs and Tatars. Simultaneous Arabic interpretation will be provided. For more on this event and to register, click HERE.  This book should come with a warning; ‘This book could change your life’, or ‘Completion of this book may trigger an instant desire to want to change the world’. ‘Americanah’ is basically a love story between a beautiful Nigerian woman called Ifemelu, and the love of her life Obinze. Preparing to travel back to Nigeria from America, Ifemelu has closed down her very successful blog about race and ended her relationship with the perfect boyfriend Blaine, an African American professor who ‘taught ideas of nuance and complexity in his classes’ at Princeton and who kissed and ‘held her tightly as though Obama’s victory was also their personal victory’. Ifemelu’s heart though lies in Nigeria and particularly with Obinze, who is a charismatic, sensitive, and now very wealthy man. However, he is married to someone else, and has children of his own. Having ended their relationship abruptly fifteen years ago, after a horrendous incident in America, Ifemelu and Obinze are now forced back into each other’s lives and feel they owe it to each other to attempt a kind of closure; a task that seems near impossible with the many experiences they have lived and the secrets they both carry. However, as Ifemelu points out in the novel, “Why did people ask "What is it about?" as if a novel had to be about only one thing.” And so as a second attempt I would tell that this novel is a deep and as close to an honest account as there ever will be of the complex, and intriguing issue of race in the United States as recorded by a Non-American African whose rude awakening to the fact that her skin colour is an issue changes her life forever. Spurred on by the idiosyncrasies around her, Ifemelu writes a blog called ‘Raceteenth’ in which she airs her grievances and shares funny anecdotes regarding life in America. “The only reason you say that race was not an issue is because you wish it was not. We all wish it was not. But it’s a lie. I came from a country where race was not an issue; I did not think of myself as black and I only became black when I came to America’. And in several of the posts, which are the best part of the book and the most dynamic, she writes, ‘Oppression Olympics is what smart liberal Americans say to make you feel stupid and to make you shut up. But there IS an oppression olympics going on. American racial minorities - blacks, Hispanics, Asians and Jews - all get shit from white folks, different kinds of shit but shit still. Each secretly believes that it gets the worst shit. So, no, there is no United League of the Oppressed. However, all the others think they're better than blacks because, well, they're not black.” And the posts go on and on and get only better and better. ‘Americanah’ is the term given to Nigerians when they return back from America. Thus another layer of the novel sheds light on the life of the privileged successful few and how they are looked upon and treated by their fellow compatriots when they return to their homeland. Those who have left are torn between longings for all that they missed while away and yet return unable to make peace with what their country has become. So they moan, grumble and complain about their beloved Nigeria but even that is conflicted when it comes to Ifemelu, ‘She was comfortable here, and she wished she were not. She wished, too, that she were not so interested in this new restaurant, did not perk up, imagining fresh green salads and steamed still-firm vegetables. She loved eating all the things she had missed while away, jollof rice cooked with a lot of oil, fried plantains, boiled yams, but she longed, also, for the other things she had become used to in America, even quinoa, Blaine's specialty, made with feta and tomatoes’. And so the answer to what ‘Americanah’ is about is quite a complex one. It is about the concept of ‘home’ and what it has come to mean in the modern world where people will do anything to leave their birthplace, not because of war and torture, famine or starvation, but because of choicelessness. It is about raising a family in a world that is foreign and totally contrary to everything that one has been taught, governed by rules that are not only unfamiliar and border on the absurd but also come mired in injustice. It is about the naïve belief that your fellow men might offer refuge and assistance for the sole reason that you grew up on the same street or went to the same school or spoke the same language. It is about the absurdity of a society where you are seen as humble just because you refuse to exercise the right to rudeness and arrogance that comes with being affluent and powerful. It is a look at how America regards its immigrants and how America is judged in return. The entire novel is a lesson in asking questions, being better informed and aware of things around us and how what we say and what we do contribute ultimately to the collective narrative that will define who we are and what we stand for as nations. And Ifemelu seems to suggest advice for the reformation: ‘If you don’t understand, ask questions. If you’re uncomfortable about asking questions, say you are uncomfortable about asking questions and then ask anyway. It’s easy to tell when a question is coming from a good place. Then listen some more’. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie will be a guest speaker at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature in March 2015. To listen to her inspiring and mesmerising TED speech "We Should All be Feminists" click on the video below. Related Article: David Oyelowo to Star With Lupita Nyong’o in ‘Americanah’  Annual book exhibition @ Gallery Ras Al Ain kicks off in Amman, Jordan this Saturday 24 Jan. The three-day event, that runs from 10am-10pm, in downtown Amman will host several Jordanian and arab authors who will be signing copies of their latest releases. The exhibition is a great chance for readers of all ages to get their hands on a diverse selection of old and recent releases that range from novels, to philosophy, religion, art and many others in both Arabic and English. There will also be a specialized children’s corner as well as unpriced books, meaning the customers pay at their own discretion. The move comes in a bid by organizers who hope this will help people who are at the exhibition to stock up new titles for their home library. The exhibition is being promoted as a showcase for new talent as well as the place to head to for the latest published works by regional authors as well as international ones. Authors and poets expected to attend include Ibrahim Nasrallah, Qassem Tawfiq, Ayman Al Ottoom, Ahmed Hassan Al Zou’bi, Hisham Al Akhras, Samira Kilani, Subhi Fahmawi, Gazi Maraqa, Bahaa’ Gharaybeh and many more. Ras Al Ain Gallery & Hangar Ali Bin Abi Talib Street, Opposite to Al Hussein Cultural Center, Amman, Jordan. Tel:064736753

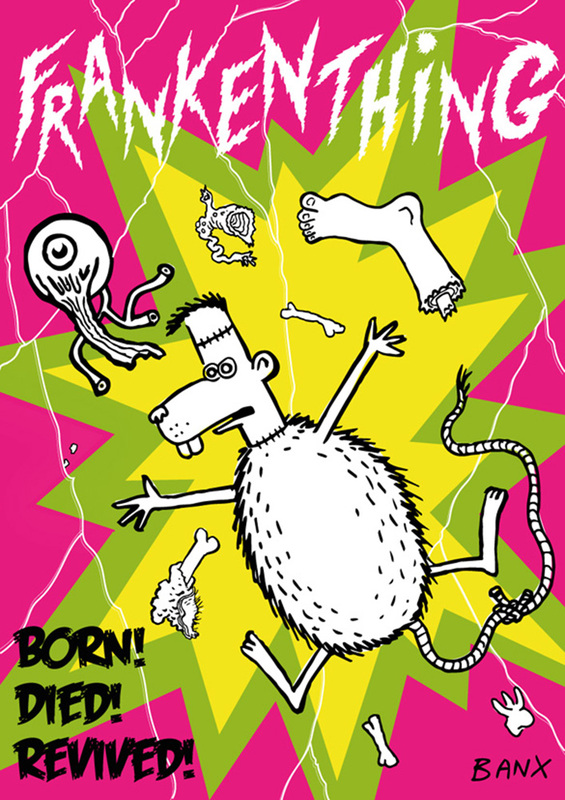

Frankenthing and the Monster become great friends; They play and laugh and dance. But Igor is lurking waiting for his chance. He had enjoyed killing Frankenthing so much the first time that he can’t wait to get his teeth and claws stuck in him again. The book has been through quite a journey before its publication and Jeremy has promised a quick Q&A to tell us all about that. This will be posted next week along with a short review of the book. In the meantime, why not download it (click HERE) and let me know what you think. To know more about Jeremy Banx and his work, click HERE

On twitter: @banxcartoons) On Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/TheReaper/944630762220816  Iraqi scholar, poet and translator, are just some of the many titles that Sinan Antoon is known for. He has now added winner of the 2014 Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation for the translation of his own novel 'The Corpse Washer' published by Yale University Press. Antoon is currently associate professor at Gallatin School of Individualized Study, New York. 'The Corpse Washer' is a novel about Iraq. Young Jawad, born to a traditional Shi'ite family of corpse washers and shrouders in Baghdad, decides to abandon the family tradition, choosing instead to become a sculptor, to celebrate life rather than tend to death. He enters Baghdad’s Academy of Fine Arts in the late 1980s, in defiance of his father’s wishes and determined to forge his own path. But the circumstances of history dictate otherwise. Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship and the economic sanctions of the 1990s destroy the socioeconomic fabric of society. The 2003 invasion and military occupation unleash sectarian violence. Corpses pile up, and Jawad returns to the inevitable washing and shrouding. Trained as an artist to shape materials to represent life aesthetically, he now must contemplate how death shapes daily life and the bodies of Baghdad’s inhabitants (amazon.co.uk). The judging panel comprised literary translator and joint winner of the 2013 Prize Jonathan Wright, translator and writer Lulu Norman, broadcaster and writer Paul Blezard, and Banipal editor and trustee Samuel Shimon. They met in December 2014 to select the winning titles from 17 entries, under the chairmanship of Paula Johnson of the Society of Authors. For more on this story, click HERE. For more about the Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation, click HERE. Let's face it! it's not everyday that I can type in a headline like this considering the generally warm weather of the UAE. So, if the weather's gone off course, surely you can too. Here are 4 things you can do as you wait for the sun to come out. Enjoy!

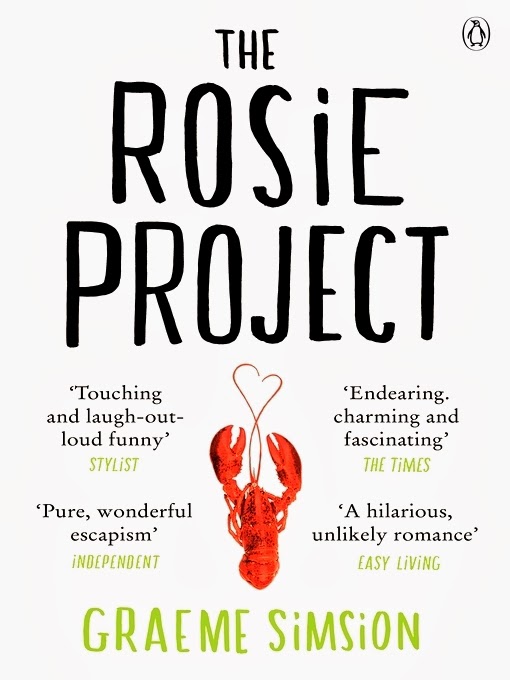

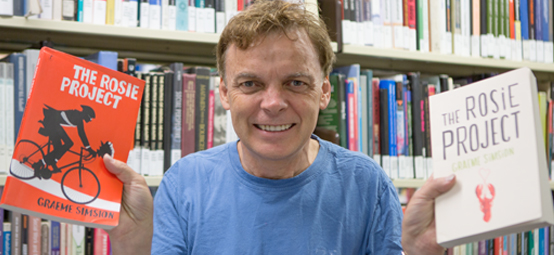

However things are about to change especially after ‘The Apricot Ice-cream Disaster’ while on a date with Elizabeth, the computer scientist, proves to be the final straw forcing Don to abandon the ‘traditional dating paradigm’ because the ‘probability of success did not justify the effort and negative experiences’ of being out with women who clearly did not get him. And with that the ‘Wife Project’ questionnaire is born. A questionnaire designed to filter out female candidates in order to locate Don’s ‘perfect woman’. It is while Don is engrossed in securing candidates for his questionnaire that Rosie steps into his life. Establishing from the start that Rosie is the complete and absolute opposite of everything that he is looking for in the perfect woman and regardless of the great time he has with her on the first day that they meet, he still resolves never to see her again, because that would be ‘in total contradiction to the rationale for the Wife Project’. However, Rosie is on a quest to uncover her biological father and asks for Don’s help. He agrees and so the ‘Father Project’ is launched. The duo’s decision to embark on this project predictably lands them into comical, at times dangerous situations that only serve to bring this very unlikely couple closer together.

The International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) has today revealed the longlist of 16 novels now a step closer to winning the 2015 prize. Those selected were chosen from 180 entries from 15 countries, all published within the last 12 months.

The 2015 longlisted authors come from nine different countries, with the highest numbers from Lebanon and Egypt, with three authors apiece. Five women appear on the longlist, the highest number so far. 11 women in total have been longlisted for the Prize since its inauguration in 2009. The full 2015 longlist is as follows: 'A Suspended Life', Atef Abu Saif, Palestine, Al-Ahlia 'Far from Clamour, Close to Silence', Mohammed Berrada, Morocco, Le Fennec 'Drowning in Lake Morez', Antoine Douaihy, Lebanon, Dar al-Mourad 'The American Neighbourhood', Jabbour Douaihy, Lebanon,Saqi Books 'Floor 99', Jana Elhassan, Lebanon, Difaf Publications 'Diamonds and Women', Lina Huyan Elhassan, Syria, Dar al-Adab 'Don't Tell Your Nightmare!', Abdel Wahab al-Hamadi, Kuwait,Al-Markez al-Thaqafi al-Arabi 'Female Voices' Maha Hassan, Syria, Dar Tanweer, Lebanon 'Riyam and Kafa', Hadia Hussein, Iraq, Arab Institute for Research and Publishing 'Sharp Turning', Ashraf al-Khamaisi, Egypt, Al-Dar al-Masriya al-Lubnaniya 'Graphite', Hisham al-Khashin, Egypt, Maktabat al-Dar al-Arabiyya lil Kitab 'The Italian', Shukri al-Mabkhout, Tunisia, Dar Tanweer, Tunis 'Willow Alley', Ahmed al-Madeeni, Morocco, Al-Markez al-Thaqafi al-Arabi 'The Daughter of Suslov', Habib Abdulrab Sarori, Yemen, Saqi Books 'The Size of a Grape', Muna al-Sheemi, Egypt, Al-Hadara 'The Longing of the Dervish', Hamour Ziada, Sudan, Dar al-Ain The shortlist will be announced on Friday Feb.13, 2015 at the Casablanca International Book Fair. Now in its 8th year, the IPAF is recognised as the leading prize for literary fiction in the Arab world. The winner of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction 2015 will be announced at an awards ceremony in Abu Dhabi on Wednesday 6 May, the eve of the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair. The six shortlisted finalists will receive $10,000, with a further $50,000 going to the winner. Delivering on its aim to increase the international reach of Arabic fiction, the Prize has guaranteed English translations for all of its winners: Bahaa Taher (2008), Youssef Ziedan (2009), Abdo Khal (2010), joint winners Mohammed Achaari and Raja Alem (2011), Rabee Jaber (2012), Saud Alsanousi (2013) and Ahmed Saadawi (2014). Taher’s 'Sunset Oasis' was translated into English by Sceptre (an imprint of Hodder & Stoughton) in 2009 and has gone on to be translated into at least eight languages worldwide. Ziedan’s 'Azazeel' was published in the UK by Atlantic Books in April 2012, while 2013 saw the publication of Spanish translations of Baha Taher's 'Sunset Oasis' (El Oasis) and Rabee Jaber's 'The Druze of Belgrade' (Los Drusos de Belgrado) by Madrid-based publisher Turner. More recently, English translations of Abdo Khal and Mohammed Achaari’s winning novels both appeared on bookshop shelves in 2014, published by the Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation. Both Raja Alem’s novel, 'The Dove’s Necklace' (Duckworth, March), and Saud Alsanousi’s 'The Bamboo Stalk' (Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing, June) will be published in the UK this year. It has also just been announced that the 2014 winner, 'Frankenstein in Baghdad' by Ahmed Saadawi, has secured English publication with Oneworld in the UK and Penguin Books in the US. It is set to be published in Autumn 2016, translated into English by Jonathan Wright. Article Source: http://www.arabfiction.org Author David Walliams Set To Appear At Dubai's Emirates Airline Festival of Literature 201510/1/2015 David Walliams, comedian, 'Britain's Got Talent' judge, actor, and children's award-winning author who has won the UK's National Book Awards' 'Children's Book of the Year' for three years in a row, will be appearing as a guest at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature 2015. The author, who has written 'Gangsta Granny', 'The Boy in the Dress' and most recently 'Awful Auntie' among many others, will be addressing his audience regarding different aspects of his career in the theatre of The Cultural and Scientific Association in Al Mamzar, Dubai, on Saturday, February 28 @ 3pm. The event is open to all ages. Tickets for the event are on sale now on the Festival website but only for 'friends' of the festival. General public tickets will be available from January 15. For more information on David Walliams and his books, check out his fun and engaging website: World of David Walliams Controversial French book 'Submission' Released

Costa Poetry Prize 2014 win prompts Book Re-print

by Rana Asfour These days whenever someone asks me to suggest a book, the first title that jumps to my mind is Jenny Nordberg’s 2014 release ‘The Underground Girls of Kabul’. I guarantee that even those of you who prefer the non-fiction genre will be nothing less than spellbound. Riveting, engaging and very beautifully written, it reads like a work of fiction with the added bonus of being completely true. Here comes a book with a refreshing take on an exhausted subject: Afghanistan. ‘The Underground Girls of Kabul’ offers insight into Afghanistan’s never-before acknowledged societal practices: the “Bacha Posh’; children born female, yet raised and treated as a male until the age of puberty at which time they are expected to revert back to their natural gender in time for marriage. Jenny Nordberg follows the bacha posh through childhood, puberty, married life and childbirth attempting to examine ‘the profound effects the practice has had on generations of Afghan women and what it means for girls everywhere’. I had never heard or come across the ‘bacha posh’ before. And it seems the author herself stumbled onto the subject quite by accident as well. An investigative journalist, she had been researching a television piece on Afghan women waiting to interview a female member of the country’s fairly new parliament to ask her about how it felt to be a woman in Afghanistan. It is as she waits to speak to Azita who is on the phone, and while playing with Azita’s twin girls in the next room, that Mehran, aged six, in bright red denim shirt and blue pants, ‘chin forward, hands on hips, swaggers confidently into the room, looking directly’ at Nordberg and pointing a toy gun in her face. Mehran, a seemingly confident boy, with black hair like his sisters, only short and spiky, is in fact ‘Mahnoush’, a girl. That there is little knowledge of the practice, an ‘anomaly’ as one Afghani diplomat told Nordberg, should come as no surprise to anyone who truly knows and understands the region explains Carol Lu Duc. Carol has been a resident of Afghanistan since 1989 and has for almost two decades worked for nongovernmental organizations and as a consultant to government ministries. She explains to Nordberg that ‘the reason that no one seems to have documented any historical or contemporary appearance of little girls dressing as boys is entirely understandable. Even if they should exist, little documentation has survived Kabul’s various wars and revolving-door regimes’. The bacha posh are treated as privileged children. They are after all responsible for elevating the status of their families and bringing in extra income as their role now allows them to go out and assist the men in providing for the family. This is a rare opportunity (if it could be called that) to play outside, wear pants, ride in the front seat, address men, and even shout in public. In a society where patriarchal rules dominate the roost, they are privy to a world that, as a girl, they will never experience. In only the rarest cases, is this arrangement permanent, for once puberty commences, pants are traded for the burqa and matters go back to how they would have been before. The girls are now obligated to shed the role of ‘boy’ in preparation for the role of ‘housewife’ and then ‘mother’. Understandably, Nordberg writes, it is not always an easy transition. Not only do women such as Shukria in the book struggle with the idea of her gender reversal and the impact it has on her freedom, but what was ‘most disturbing’ to her after she was transformed back, to be married, was her ‘inability to perform the most basic female tasks’ she was told would come naturally; ‘Dinner was served raw or burned, laundered clothes were not clean’. When she worked on her exterior, things were no better and the all-female gatherings ‘made her extremely nervous and embarrassed’. And yet she endured. Others have not been so lucky battling with occasional bouts of depression and suicide attempts. However, the full gravity of such a practice has yet to be studied. The focus of the book is the bacha posh but it is also an insightful study into the lives of the women who make such a practice possible. The mothers. Nordberg’s documentation of the intricate details of the lives these women lead, the conversations she records, the joys and the upheavals she witnesses firsthand are poignant examples that dispel any belief once held regarding the rhetoric justifying war on a country to ‘save’ its women. In the interviews dispersed throughout the book we get the honest, sometimes brutal, reality of what it is to be a woman in Afghanistan. The discussions with the author are quite revelatory, surprising, even amusing at times, and some readers, I’m sure, will find certain ‘truths’ of how Afghani women really think quite hard to make peace with. In a chapter entitled ‘Men’, Nordberg writes about the ‘interesting concept’ of freedom. In a rudimentary questionnaire in which she asks Afghani men what differentiates them from the women, they often describe women ‘as sensitive, caring and less physically capable’. Yet, when the same question is posed to women, the answer, regardless of who they are, rich or poor, educated or illiterate, is ‘one word: Freedom. As in men have it, and women don’t’. However, as with everything in Afghanistan, even a simple answer such as this is never what it first appears to be. Further investigation reveals that what Afghani women define as freedom can be at odds with the notions of equality and freedom preached to them by ‘Western and European specialists shuttled into the country into so-called ‘gender workshops’ taking place at upscale hotels in Kabul by women in ethnic jewelry and embroidered tunics drawing circles on whiteboards around words like ‘empowerment’ and ‘awareness’’’. ‘The Underground Girls of Kabul’ is a powerful and important book that should be read by everyone. It is an honest account of what happens to a part of society when cowered by a more dominant one. Extreme brave practices such as the bacha posh that defy the status quo will continue to show in societies until a time ‘someday in our future it may be possible for women everywhere not to be restricted to those rules society deems natural, God-given, or appropriately feminine’. The solutions Nordberg proposes for a change in attitudes are engaging and provide food for thought indeed. But you’ll have to read the book to find out what they are.  by Rana Asfour It was Destiny that made me choose to read this book on New Year’s Eve. Melodramatic words to start a review, when at my age, I should know better. And yet, ‘like a teenager, I too can rebel’, I too can change the rules with which to start a review. For there is nothing ‘un-dramatic’ or even slightly ordinary about Rabih Alameddine’s latest novel, ‘An Unnecessary Woman’. Aaliya Sobhi Saleh is a seventy two-year-old divorced retiree who has lived all her life in Beirut. She begins her tale ‘with a badly lit reflection. One of the bathroom’s two bulbs has expired’ where she stands with a dye job gone wrong (percolating remembrance, red wine, an old woman’s shampoo: mix well and wind up with blue hair), a toothbrush in hand looking at a murky image of herself reflected in the only mirror in the entire house. A smudged mirror she rarely cleans. Her sink, by contrast, is immaculately white; its bronze faucets sparkle. And so, ‘we do not need to consult Freud or one of his minions to know that there’s an issue here’. A former bookseller at a not-so-busy bookshop, Aaliya since the age of twenty-two has ‘begun a translation every January first’. An autodidactic, who has long ago abandoned herself ‘to a blind lust for the written word’ Aaliya has managed to translate several works of literature into the Arabic language. What is intriguing about all this is that she has told no one what she does nor shown her finished work to anybody. The completed works eventually end up in a labeled carton box that is later stored in the empty maid’s room and bathroom; ‘I create and crate’. Aaliya is alone. A deceased ex-husband, her only friend dead, she childless and distanced from her mother and step-family, a recluse uninterested in the company of others preferring isolation. She is an obstinate, determined, highly observant, feisty, witty, unapologetic grumpy old woman with a lot of oomph (all attributes Aaliya would most likely scoff at were she real). Aloneness, after all, was a choice she made yet it was also ‘a choice made with few other options available. Beiruti society wasn’t fond of divorced, childless women in those days’. Aaliya lives in Beirut, where teenagers hang out at Starbucks ‘lounging in seemingly uncomfortable and unsustainable positions’, a Beirut where ‘traffic war’ rages and ‘chaos rules’, where ‘dating, premarital cohabitation, adultery and promiscuity became ordinary painted scenes of the current Beiruti landscape’. This is a Beirut that ‘belongs to the young and their apathy. That is no country for old men. Or old women for that matter’. So, it is in the solace of her home library that Aaliya is truly herself. Among her books and authors and poets and composers. And what an enviable collection that is. It is in these parts of the book that voracious readers will feel that they are in fact in the presence of greatness. Aaliya may feel like her family’s ‘unnecessary appendage’, yet as keeper of books she is a Goddess among Gods. Tolstoy, Gogol, Hamsun. Gordimer, Malouf, Kundera, and Kadera. And so many more still. It is through books (and an AK-47), that Aaliya has survived her life. Books show her ‘what it’s like to live in a reliable country where you flick on a switch and a bulb is guaranteed to shine and remain on’. And while an insane Lebanese civil war raged on and ‘young men in perfectly clean uniforms were able to shoot people while gnawing on a kebab sandwich and sipping Pepsi’ it was between the covers of books that she found comfort. When ‘the glow of Sabra burning illuminated Beirut’s skyline’ it was Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ she read because ‘someone had to’. And it is a Pessoa quote that is at the forefront of her mind when she comes face to face with her first corpse. And while her city was ‘self-immolating’ she was busy teaching herself how to listen to music. Aaliya is suffering a crisis that she knows not the cause of. ‘A creature of habit’ she abhors change, doesn’t adapt well to it. Her blue hair, her senile ‘modern-day succubus’, screaming mother unexpectedly showing up at her doorstep, her neighbors (the three witches) living in her building who turn saviors, the rain, the persistent insomnia with the memories that come flooding uninvited are proving overwhelming. Aaliya is tired and only wants to rest. The long nights are occasions to question her beliefs, her thoughts on life, art, reading. Unbidden memories resurface and ghosts awaken as if from a deep slumber. However, it is ‘the loneliness, the abject isolation’ that is a reminder of ‘how utterly ‘inconsequential’ her life has become, ‘how sad’. ‘An Unnecessary Woman’ is not an easy read (with often harsh quite brutal truths and observations) and yet it is not one that you will want to read through quickly anyway. Each sentence is meticulously constructed, each word deliberate and in its exact place, and the result is a work of beauty and ingenuity. This book is for those who ‘live for art’, it is for survivors of atrocities who can still find beauty in the extremely grotesque. It is about love (for oneself, for others, for beauty, for ugliness), loss (of country, freedom, choice, hope), redemption, aging and death. It is about music, writing, and God. It is about Beirut, past and present, from someone who knows Beirut ‘how she was, how she has changed through the years’ from the lips of a woman who has ‘never left her’.  by Rana Asfour Robert Thorogood's new murder mystery novel 'A Meditation on Murder: A Death in Paradise Novel' has been released for download on Kindle. Thorogood is the creator and writer of The Caribbean crime drama on BBC1's "Death in Paradise", starring Kris Marshall, Sara Martins and Gary Carr. With the book's namesake, TV hit series 'Death in Paradise' entering its 4th season, the book had already accumulated hype and a large fan base ready to devour each and every word before it every hit the shelves. The story: Aslan Kennedy has an idyllic life: Leader of a Spiritual Retreat for wealthy holidaymakers on one of the Caribbean's most unspoilt islands, Saint Marie. Until he’s murdered, that is. The case seems open and shut: when Aslan was killed he was inside a locked room with only five other people, one of whom has already confessed to the murder. Detective Inspector Richard Poole is hot, bothered, and fed up with talking to witnesses who’d rather discuss his ‘aura' than their whereabouts at the time of the murder. But he also knows that the facts of the case don’t quite stack up. In fact, he’s convinced that the person who’s just confessed to the murder is the one person who couldn’t have done it. Determined to track down the real killer, DI Poole is soon on the trail, and no stone will be left unturned. 'Death in Paradise' the TV series will air January 9th, 9pm on BBC1 by Rana Asfour

First day of the New Year and again I stand where I have stood countless times before. In front of the mirror having a heart-to-heart with the reflection staring me smack in the face. With a knowing look in its eyes, it knows that what has brought me here, to this déjà vu, has a lot to do with the fact that I’ve just finished photocopying last year's 'resolutions' list. ‘Here we go again’ it sighs, oblivious of the master plan taking shape in my mind. The reflection follows my every move as I tape a Facebook photo onto its periphery. A photo taken of me at a ‘White Christmas’ party just over a week ago, revealing my spreading weight in all its glory. Stealing a furtive glance towards my nemesis, its eyes seem to accuse me of deceit, ‘Really?’ it smirks, ‘You had no idea it was this bad?’ ‘No.’ I reply. ‘I really didn’t’. Emboldened now, I take a long hard look at my spit image, visualise it shrinking before my very eyes. I witness the flicker of something akin to bewilderment, then fear, and finally acquiescence of what will be will be. With the message definitely conveyed, a flying kiss seals the deal. I turn away but not before uttering my first ‘goodbye’ of the year. |

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed