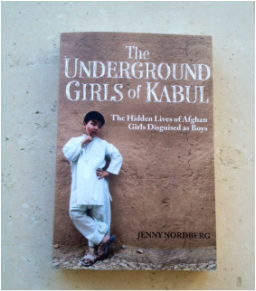

by Rana Asfour These days whenever someone asks me to suggest a book, the first title that jumps to my mind is Jenny Nordberg’s 2014 release ‘The Underground Girls of Kabul’. I guarantee that even those of you who prefer the non-fiction genre will be nothing less than spellbound. Riveting, engaging and very beautifully written, it reads like a work of fiction with the added bonus of being completely true. Here comes a book with a refreshing take on an exhausted subject: Afghanistan. ‘The Underground Girls of Kabul’ offers insight into Afghanistan’s never-before acknowledged societal practices: the “Bacha Posh’; children born female, yet raised and treated as a male until the age of puberty at which time they are expected to revert back to their natural gender in time for marriage. Jenny Nordberg follows the bacha posh through childhood, puberty, married life and childbirth attempting to examine ‘the profound effects the practice has had on generations of Afghan women and what it means for girls everywhere’. I had never heard or come across the ‘bacha posh’ before. And it seems the author herself stumbled onto the subject quite by accident as well. An investigative journalist, she had been researching a television piece on Afghan women waiting to interview a female member of the country’s fairly new parliament to ask her about how it felt to be a woman in Afghanistan. It is as she waits to speak to Azita who is on the phone, and while playing with Azita’s twin girls in the next room, that Mehran, aged six, in bright red denim shirt and blue pants, ‘chin forward, hands on hips, swaggers confidently into the room, looking directly’ at Nordberg and pointing a toy gun in her face. Mehran, a seemingly confident boy, with black hair like his sisters, only short and spiky, is in fact ‘Mahnoush’, a girl. That there is little knowledge of the practice, an ‘anomaly’ as one Afghani diplomat told Nordberg, should come as no surprise to anyone who truly knows and understands the region explains Carol Lu Duc. Carol has been a resident of Afghanistan since 1989 and has for almost two decades worked for nongovernmental organizations and as a consultant to government ministries. She explains to Nordberg that ‘the reason that no one seems to have documented any historical or contemporary appearance of little girls dressing as boys is entirely understandable. Even if they should exist, little documentation has survived Kabul’s various wars and revolving-door regimes’. The bacha posh are treated as privileged children. They are after all responsible for elevating the status of their families and bringing in extra income as their role now allows them to go out and assist the men in providing for the family. This is a rare opportunity (if it could be called that) to play outside, wear pants, ride in the front seat, address men, and even shout in public. In a society where patriarchal rules dominate the roost, they are privy to a world that, as a girl, they will never experience. In only the rarest cases, is this arrangement permanent, for once puberty commences, pants are traded for the burqa and matters go back to how they would have been before. The girls are now obligated to shed the role of ‘boy’ in preparation for the role of ‘housewife’ and then ‘mother’. Understandably, Nordberg writes, it is not always an easy transition. Not only do women such as Shukria in the book struggle with the idea of her gender reversal and the impact it has on her freedom, but what was ‘most disturbing’ to her after she was transformed back, to be married, was her ‘inability to perform the most basic female tasks’ she was told would come naturally; ‘Dinner was served raw or burned, laundered clothes were not clean’. When she worked on her exterior, things were no better and the all-female gatherings ‘made her extremely nervous and embarrassed’. And yet she endured. Others have not been so lucky battling with occasional bouts of depression and suicide attempts. However, the full gravity of such a practice has yet to be studied. The focus of the book is the bacha posh but it is also an insightful study into the lives of the women who make such a practice possible. The mothers. Nordberg’s documentation of the intricate details of the lives these women lead, the conversations she records, the joys and the upheavals she witnesses firsthand are poignant examples that dispel any belief once held regarding the rhetoric justifying war on a country to ‘save’ its women. In the interviews dispersed throughout the book we get the honest, sometimes brutal, reality of what it is to be a woman in Afghanistan. The discussions with the author are quite revelatory, surprising, even amusing at times, and some readers, I’m sure, will find certain ‘truths’ of how Afghani women really think quite hard to make peace with. In a chapter entitled ‘Men’, Nordberg writes about the ‘interesting concept’ of freedom. In a rudimentary questionnaire in which she asks Afghani men what differentiates them from the women, they often describe women ‘as sensitive, caring and less physically capable’. Yet, when the same question is posed to women, the answer, regardless of who they are, rich or poor, educated or illiterate, is ‘one word: Freedom. As in men have it, and women don’t’. However, as with everything in Afghanistan, even a simple answer such as this is never what it first appears to be. Further investigation reveals that what Afghani women define as freedom can be at odds with the notions of equality and freedom preached to them by ‘Western and European specialists shuttled into the country into so-called ‘gender workshops’ taking place at upscale hotels in Kabul by women in ethnic jewelry and embroidered tunics drawing circles on whiteboards around words like ‘empowerment’ and ‘awareness’’’. ‘The Underground Girls of Kabul’ is a powerful and important book that should be read by everyone. It is an honest account of what happens to a part of society when cowered by a more dominant one. Extreme brave practices such as the bacha posh that defy the status quo will continue to show in societies until a time ‘someday in our future it may be possible for women everywhere not to be restricted to those rules society deems natural, God-given, or appropriately feminine’. The solutions Nordberg proposes for a change in attitudes are engaging and provide food for thought indeed. But you’ll have to read the book to find out what they are.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed