|

by Rana Asfour Daniel José Alder, a BuzzFeed contributor, wrote in a 2014 online article that ‘we are always writing 'the other', we are always writing the self. We bump into this basic, impossible riddle every time we tell stories. When we create characters from backgrounds different than our own, we’re really telling the deeper story of our own perception. We muddle through these heated discussions at panels, in comments sections, on social media, in classrooms — the intersections of power and identity, privilege and resistance. ‘How,’ he questions, ‘do we respectfully write from the perspectives of others?’

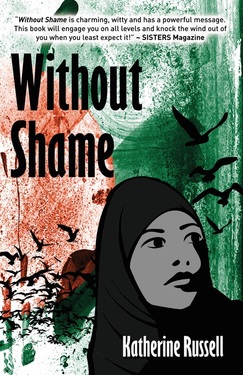

The reason I bring this up is that FB Publishing, a small-press publishing house that works with Muslim authors, topics and stories will this month be releasing a new book ‘Without Shame’ by author Katherine Russell. The delightful story of a Pakistani/Bengali girl called Sariyah living in East Pakistan during the unsettled period of 1968 when the Bengalis were not only calling for but were also preparing for a revolt to secure the independence of Bengal from Pakistan. Katherine Russell has taken a big risk choosing for her debut novel to write about ‘the other’. See, she writes about Islam – particularly Sufi Islam - though she herself is not Muslim. She writes in the tongue of a woman from Pakistan and yet she herself is a white woman from Buffalo NY. However, what Russell is is a double lung transplant survivor who frequently writes about her experiences with cystic fibrosis and a seasoned writer whose other writing themes include, in addition to exploring other cultures, challenging the American criminal justice system, and social change. She is also a poet. On her website ‘Katherinekeepswriting.com’, Russell has been very upfront about some of the reasons she wrote “Without Shame’ one of which she believes is that ‘as people read about other cultures and religious nuances, they will be MORE equipped to distinguish religious practices from cultural tradition and not make generalizations about entire religious groups on a global scale’. ‘This is a fundamental tenet of my book,’ she writes. ‘Culture is inseparable from religion - they are a part of each other. When East and West Pakistan were formed, it was based on a theory that all Muslims were the same, so they should live under the same Pakistan. Let's take a guess if that worked...’ In Sariyah’s village, ‘shame is a virtue she never mastered’. As a child, her first act of defiance left her with a lifelong limp serving as an everyday reminder of the shame she brought on herself and her family. However, defiant Sariyah, unhindered by her oppressive father’s views regarding the role of women in society, takes a job as maid at Martin House, a boarding house for volunteer American teachers. Her father's grudging acquiescence comes on the back of his resentful knowledge that Sariyah's 'capacity to do work was unhindered by the limp; however, her capacity to carry a baby was uncertain' which meant her prospects of a marriage proposal were close to none. And yet, Sariyah will have to make one more sacrifice still to ensure that her limp does not stand in the face of her beautiful much coveted sister Nisha, who is adamant on securing a profitable marriage. At Martin House Sariyah meets Rodney, a young American struggling with the guilt of past decisions. A friendship develops between these two very different characters. Whereas Sariyah views her every step in life as one that brings her closer to God, Rodney on the other hand views the world ‘in polar distinctions: of freedom and what hinders it, of knowing and not knowing, of truth and falsehood’. And yet the two young people’s interest in each other’s worlds gradually progresses into a romantic one of sorts in which Sariyah chooses to conceal her complicated engagement to the loathsome man of her father's choosing. When Rodney suddenly falls violently ill, Sariyah decides to break her father’s wishes as she rushes to seek help from the uncle he has forbidden her to ever have contact with. When Rodney recovers he finds himself drawn to the old man Sajib, from whom he begins to learn the ways of the Bengal people. Soon, Rodney discovers a few harsh truths not only regarding the country he has set his mind to ‘understanding’ but he finds himself being challenged by Sajib with regards to his belief system and his Westernization. When his confusion shows and he is at a loss of words Sajib steps in to reassure the young man that it is 'hard for the mind to adjust to a new place without wanting to force the familiar on it’ and as eager as Rodney is to learn of the ways of this country he has voluntarily chosen to be in, he shows resistance whenever religion is brought up. Sajib with his wizened ways prods Rodney on: ‘Come see who we are and what moves our limbs in the morning, what summons us from the escape of dreams to give thanks for our struggle. What makes us surrender our notions that the world owes us, not the other way around. I am not asking you to become us, but to know us’. Katherine Russell has done a very fine job with her novel. The characters are plausible and the events as well as the themes the novel touches upon will provide many interesting discussion points among readers. Although it is clear that a lot of research has been done and she has taken great pains to be respectful of her subject matter, this sadly in no way means that she is exempt from inadvertent prejudiced stereotyping in a few instances. But hey, no one ever is. And for those of you who might disagree with this last sentence my advice is to think along the lines of stones and glass windows. That said, this is not the book that will teach you about Islam, Pakistan, Bengal or provide insightful research-worthy material with regards the female situation in that part of the world. But here’s the point. It never claimed to be. What the author is offering is a work of fiction, a story, a stepping out from our everyday reality wherever in the world we may be in order to spend a few hours with her make-believe characters; ones she has superbly moulded and shaped to evoke a myriad of emotions; empathy, love, betrayal, denial, anger, identity and hope. 'Literature is supposed to reveal a part of life,' writes Katherine Russell about her new release on her website. 'It is not definitive, it is not the template of all reality. It is a peephole into someone else's truths. It is an insight into our connection, our differences, our humanity. It is supposed to show, not dictate. Hopefully, through that, we can become a more tolerant, empathetic, and loving people'. And for those who choose to believe otherwise, her response is ready too: 'Those who will read it will take it as they will'. And I couldn't agree more! Back Cover: East Pakistan, 1968: In Sariyah’s village, shame is a virtue she never mastered. As a child, she learned to read in secret, kept talismans against her father’s orders, and questioned everything, even Allah. Now she is practicing how to be a “woman with shame,” torn between promises to her family and to herself. She yearns to join a movement with her fellow Bengalis, who are gripping onto their language and cultural identity against colonial powers – but she is continuously sucked into the narrow visions of her father. In the midst of all this, an American has come to teach English. Rodney Creed comes with the bright optimism of a college graduate, too eager to sense the rumbling ground beneath him – until he meets Sariyah. Rodney believes he is there to teach, but he will learn painful, irreversible things. ‘Without Shame’ is a love story at its core – but not in the traditional sense. It’s about love of one’s country, culture, God, and language. It’s about the power of identity to shine through when other forces threaten to overshadow it.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed