|

by Rana Asfour

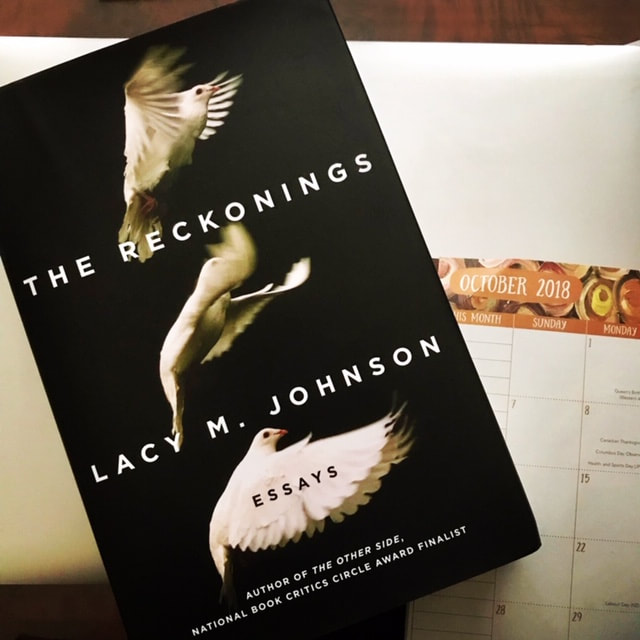

When during the Kavanaugh Hearings a few weeks ago now, Dr. Blasey Ford spoke of the two front doors she insisted on during their house’s renovation in spite of the fact that it rendered the property aesthetically unpleasing, I wasn’t surprised. That same morning I’d finished reading Lacy M. Johnson’s essay entitled ‘Girlhood in a Semibarbarous Age’, one out of the twelve-essay collection recently published by Scribner this month under the title ‘The Reckonings’. In this particular essay, the author describes her peculiar office habits. She writes: ‘I leave the lights off in the room where my desk is so I can see anyone who comes in before that person can see me. It’s one in a set of self-protective habits I have, all of which I do without thinking. There are scissors in a cup near my monitor; I keep them visible and sharp’. By now we all know that Dr. Blasey Ford’s story was about a man who she alleged had hurt her. Johnson’s story is also about a man; a man she once loved very much, so much so that when he first abused her with his words and then with his fists, she still stayed with him. ‘I told myself I could fix him,’ she writes. ‘That this wasn’t who he was, not really. I let him keep showing me who he really was until I finally believed him and left.’ In 2014, Lacy M. Johnson, penned her memoir, ‘The Other Side’ published by Tin House Books in which she wrote about being kidnapped and held in a soundproofed room in a basement apartment her boyfriend - who she had left - had rented and fitted for the sole purpose of raping and killing her. She escaped and he fled to Venezuela where he is now married and has two daughters. He has yet to face justice for his crime. Now Johnson has written ‘The Reckonings’ - a collection of self-reflective essays inspired by the recurring question she is often asked about the ‘justice’ she would like the man who hurt her to receive as well as questions about the nature of that justice in a culture obsessed with retribution. Her answer draws from philosophy, art, literature, mythology, anthropology and other fields as well as personal experience to consider how our ideas about justice might be expanded beyond vengeance and retribution to include acts of compassion, patience, mercy, and grace. In the opening essay entitled ‘The Reckonings’ which shares its title with that of the book, Johnson writes that in all the movies ‘… the person who has done a terrible thing falls from a very tall building, or is incinerated in a ball of white-hot flames, or is shot in the dark by police, or at the very least is led away in handcuffs’. None of those have been forthcoming scenarios in Johnson’s case as her assailant lives his life a free man. Nietzsche, who the author draws upon in the same essay supposes that when an assailant imposes a crime on a victim that crime becomes a debt, the criminal a debtor, the victim his creditor ‘whose compensation is the particular pleasure of bearing witness to a cruel and exacting punishment’. In layman’s terms: when someone does something bad, something bad should happen to that person in return preferably exacted by the victim. Shockingly, it is not this type of reckoning Johnson seeks for herself. That is not to say that she does not want a reckoning –she does - only not so much one that comes laden with more ‘blood, guts and gore’. She fights back against a ‘justice’ secured by ‘transforming a suffering to take a pain we experience and changing it into the satisfaction of causing pain for someone else’. ‘Would I cheer, and cry, and jump up and down if the man who kidnapped and raped me were kidnapped and beaten, if I could grind him down with my rage until there was almost nothing left of him … To be honest, I’m not sure what justice is supposed to feel like,’ she writes. The most profound message one gets from Johnson’s writing – whether you agree with her views or not, is that this is a woman who refuses to be a helpless victim who waits behind bolted doors for a hero who will bring her the reckoning all of us believe she deserves. Instead, she is the hero of her own story. This fiercely brave survivor has taken the world head on searching for her own version of a satisfying reckoning defying many who might consider her views idealistic, if not utopian particularly in the maelstrom of the increasingly aggressive rhetoric and in some instances physical violence being launched between disagreeing parties. In her case, Johnson’s reckoning manifests in the creative non fiction classes that she teaches where she encourages her students to engage in the current social and political issues of the moment in order to have an active role in forging a world where everyone can speak truth to power without fear of violent retribution or pathological apathy; it appears while on a job teaching writing in a pediatric cancer ward where she tells us the heartbreaking story of ‘the girl with the yellow wig’ that reminds us we are all human. It comes in writing about how Hurricane Harvey affected her family and how her husband risked his own life helping his neighbors as they in turn helped others. She writes of broader societal wrongs such as the BP oil spill, government malfeasance and police killings. Through all this she finds and maintains her own justice, one that makes way for joy not violence, for love not hate and one that defies the plan once hatched by a man she once loved to silence her so that it fails over and over again. As I post this today, it has already been four days since the MAGAbomber was arrested for sending homemade pipe bombs to 13 high-profile Democrats who had views that clashed with his own, and a day since the senseless deadly shooting inside a Pittsburgh Synagogue that claimed the lives of 11 innocent Jewish worshippers and injured several others because their shooter ‘hated’ all Jews. In her essay ‘Goliath’, Johnson writes that ‘we learn to see evil in others because we do not wish to acknowledge a painful truth: none of us is as good as we imagine ourselves to be … I see how we teach ourselves to hate one another and, in our hatred, to destroy. I believe in the harm that stories can do, but also in their power. If people can tell stories that cast shadows where there are none, perhaps stories can also shed light where there is darkness, and can promote an understanding where there is confusion and fear’ Two weeks ago I described ‘The Reckonings’ on my Instagram account as timely given the current political climate in the US. Today, I describe it as a crucial, essential read that offers ‘radical hope’ to kick-start an urgent conversation about the justness of America’s society and the stories its citizens tell each other. It is a conversation the American public can no longer afford to delay. As Johnson puts it, the time has come for a ‘shift in intellect, a change in perspective, a new way of seeing that is then impossible to unsee’. Lacy M. Johnson is the author of the memoir 'The Other Side' which was named a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in autobiography, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, and Edgar Award in Best Fact Crime, and the CLMP Firecracker Award in nonfiction. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Tin House, Guernica and elsewhere. She lives in Houston and teaches creative nonfiction at Rice University.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed