|

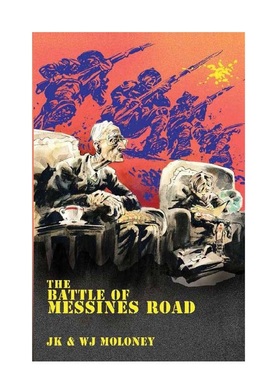

by Rana Asfour Abu Dhabi-based New Zealander William Moloney has just released his debut historical fiction entitled ‘The Battle of Messines Road’. The book is based in large part on the actual war diary of his late grandfather JK Moloney, who served on the Western front from 1915 – 1917. The diary can be found in New Zealand’s National Archives. ‘The Battle of Messines Road’ is, on the one hand, a novel about 10-year-old, Commando Comic series reader, Zac Le Burn, from Wellington, who strikes an unlikely friendship with Messines Road resident, Mr. Moloney, after a miscalculated decision by Zac on his daily paper run lands him with a ‘punishment’ that involves him reading to the nearly blind, elderly old man. On the other hand, it is, in the broader sense, a book about New Zealand’s involvement in World War I, and the lasting effects it has had on that country. Arriving for his first day at Mr. Moloney’s whose kitchen smelt ‘like bleach and damp were in a battle to the death’ and whose living room was musty and dank, he is handed a folder of papers to read about ‘a writer on a troopship, going to war’. Zac, at first uncomfortable with anything to do with the subject of war, as it not only reminds him of his father serving in Vietnam but also threatens to awaken ‘the big scary dangerous’ which Zac is in constant battle with himself to control, finds he is soon absorbed in the events of the diary. He decides that war sounded a lot ‘like school camp’ when it came to the food, the cleaning up and the rules. The readings reawaken Mr. Moloney’s long ago memories of a time that saw him on an adventure he would never have got to have but for the war. In an early journal entry in Steenbecque, France, dated 17 April, 1916 JK Moloney writes: ‘With us [New Zealanders], it is fun all the way. The saving grace of the Anzac Corps is their capacity to make the most of the shining hour. If the truth be known, this crowd absolutely enjoy the war’. Although on a more sober note, he continues, ‘Perhaps if our country were invaded, our homes destroyed and our national life upset, we might not have the same outlook’. The readings also serve to rouse a 10-year-old boy’s curiosity to learn about the places and people mentioned in the diary. A gradual kinship blossoms between the two characters as they discover that they have both started to look forward to their reading time together. Eventually, as the two hatch a plan to battle against ‘all the unfairness’, they land themselves in a spot of trouble with Mr. Moloney’s daughter and Zac’s mum, whom they have nicknamed the ‘brass hats’ as well as some boys from the neighbourhood. Not content with the magnanimous task of taking on the 'Great War', the author has chosen to set the novel in the year 1968 in which New Zealand troops are busy fighting in Vietnam; A time that saw a vocal and well-organised anti-war movement in New Zealand with many accusing the New Zealand government of simply doing what the US told it to. All this loomed large in the lives of service families making it a difficult time for army wives and their children as is very evident in Zac’s everyday dealings with those around him as well as his life at home with his mum and two siblings. ‘I was interested in the Vietnam War because I think it provides a counter point to the First World War,’ says author William Moloney. ‘The two wars are so very different, in scope, in involvement, in popularity. But in the end, they are both wars that involved New Zealand soldiers. The First World War involved or affected, in some way, every person in New Zealand. More than that, it was a war fought by a very British version of New Zealand. The Vietnam War was one fought by a professional New Zealand army. We didn’t have conscription. So, the number of troops, and their experience and their families’ experience, was very different from that of World War I when the whole country was involved. They were alone in many ways, especially as the Vietnam War was so unpopular’. 'In November, it will be fifty years since the end of the Great War. I know this seems a long time to you but it's not, not in the scheme of things. Only fifty years to change from it being shameful for not doing your duty to shameful for doing it' - Mr. Moloney to Zac. Author, William Moloney, holds a Masters degree in War Studies and as such it is highly evident that a lot of research has gone into his novel. There are so many parts that will prove illuminating and enjoyable to many readers even those, like myself, who might not necessarily, usually be drawn to the subject. It was lovely to dip in and out of the journal that alternated between the writer’s actual diaries (non fiction) and old Moloney’s running commentary (fiction) during Zac’s reading as he tries to make sense of his time at war. Since author William Moloney never met his real grandfather, who died a few years before he was born, he works around the character traits evident in the diary and spins them out to a re-imagining of what his grandfather might have been likely to be, do or say when he was older. ‘Not a better man, not a worse man, just a different man,’ says William Moloney. ‘The reason I named the character in the book Mr. Moloney was out of respect for the nature of the diary. I felt that if I changed the character’s name a link to that historical document would be lost’. As Zac’s readings go on, we find in Mr. Moloney a character trying to make sense of a war he is unable to recover from and to reconcile it with a war, that fifty years later, is shifting the country’s attitudes yet again. Mr. Moloney alternates between instances of happiness when he recalls his travels and the people he met and the places he passed through, to instances of sadness and utter desolation when he remembers the scores of young, promising lives wasted on the battle ground in a war where everyone thought they ‘were doing the right thing’ and yet was nothing less than ‘God-awful’. Ultimately, as Zac reads out the entries, readers are treated to a wealth of information that start from when Mr. Moloney boards the troopship ‘Tahiti’ in 1915 to Egypt and then all the way to the Western Front in France where he serves until 1917, when the diary ends. Throughout, JK Moloney's beautiful writing, wit, keenly observant eye, sense of humour and honesty even when it hurts to do so, come through. His recording of key historical events and first hand encounters with wartime figures is just priceless. Moloney writes of the Armenian refugee camps as well as the Prince of Wales’s visit to Alexandria in 1916. He describes his encounter with the ‘first vista of the war’ at Armentière in France, of the desolate ‘bloody, muddy ditches’ that are the trenches, and of ANZAC Day, Chunuk Bair, Gallipoli, Messines, Flers and the horror of Passchendaele. He writes of Kitchner, Ponsonby, Lloyd George, William Ham and his meeting with Rudyard Kipling and so much more. The journal offers a thorough detailed image of life during World War I not only for the soldiers but for the civilians caught in its crossfire as well. 'In Gallipoli, the boys have shown themselves to be the equal of anything the world has produced; some say they are the best ever. They did their duty like heroes and never complained' - JK Moloney, diary entry El Dabba, Christmas morning, 1915 However, it serves well, at this point, to mention that many of the accounts of the characters’ lives are fictitious and based on the author’s imagination. ‘I loved trying to piece together the lives of these men after the war but they are not fact, they are fictionalised accounts of their lives, as remembered by a shaky, and failing memory,’ he says. ‘Based on what I could find out about them, I then placed them in the mouth of an old man remembering his youth, remembering the friends of his youth. And as we all know, memories are not sacred. They are not the truth; we shape them, by our experiences, by the lives we have lived’. After a while, one gets the impression as if in fact two books run simultaneously side by side. This in no way detracts from either storyline but it was interesting to find out that, in fact, that is exactly how the novel came about in the first place. ‘I think it probably, all told, took about 12 years to write the book. I first read a photocopied diary in 2002 and so the first thing I had to do was type it out. And as it runs to about 120,000 words this took me a decade or so. I didn’t work on it everyday or even every month, what with work, kids and life. In 2011, I set proper time for it, finished the typing and started researching the stories of the men mentioned in the diary. I then tried to write a story to fit around the diary that could enhance it to give the reader context. Writing Zac’s story took 18 months to write and another six months to edit’. Apart from the theme of war, many readers will identify ‘The Battle of Messines Road’ as a novel about family, friendship, loss, and ultimately love. It is also about religion, loyalty, national identity and the rotten business that is war and politics. The two intertwined narratives will hold a wide-range of reader interest and the perspective of 10-year-old Zac will capture the attention of the young adult market while still appealing to more mature readers. According to records, it has been argued that the ‘Battle of Messines’, from whence the novel borrows its title, was the most successful local operation of World War I, certainly of the Western Front. Carried out by General Herbert Plumer, Second Army, it was launched on 7 June, 1917 with the detonation of 19 underground mines underneath the German mines. It was the first time Australians and New Zealanders had fought side by side since the Gallipoli campaign of 1915. Although the offensive initially recorded very few casualties, as the day wore on, though, German guns began to bombard the newly captured areas and many New Zealand and Allied troops were killed. By the time the New Zealand Division was relieved on 9 June, it had sustained 3700 casualties, including 700 dead. The book is out now and can be bought HERE. About the authors:

William Moloney is a 40-year-old New Zealander. He holds a BA from Massey University in History, Economics and Politics and an MA from Kings College, London, in War Studies. He has worked as a military and political analyst for the last ten years and currently resides in Abu Dhabi, UAE. He is married with three children. J.K. (Jack) Moloney was a 22-year New Zealand law-student when he left for war in 1915. After being returned to New Zealand as a casualty he lived in Christchurch, working as a barrister. During his life, he became prominent in region as a rugby and athletics administrator including being President of the Canterbury Rugby Union. He wrote several books on rugby including 'Rugby Football in Canterbury, 1929-1954 (1954) and 'The Ranfurly Shield History' (1960). He was married to Margret and had three children Barbara, Phillipa and David. He died in 1971.

3 Comments

Sam Coxhead

28/6/2015 09:29:43 am

This looks like a great read- what an incredible concept.

Reply

Edward

29/6/2015 02:47:23 pm

Reply

Kathryn

30/10/2015 06:01:32 am

Really looking forward to reading this book. You've got a mention on this blog Rana - http://childrenswarbooks.blogspot.ae/2015/07/the-battle-of-messines-road-by-j-k-w-j.html

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed