|

by Rana Asfour When in 1967, 22-year-old, LSE graduate, Julia ‘did as she was told’ and resigned from her first proper job to marry diplomat Oliver Miles, little was she prepared for the roller coaster lifestyle of British diplomatic life.

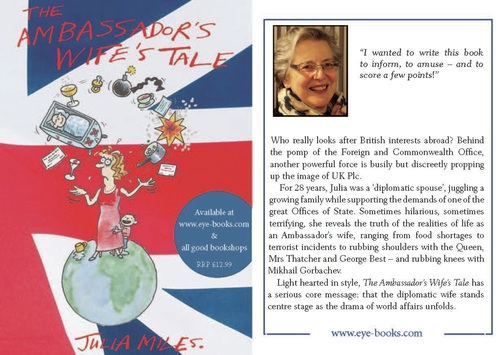

The couple had met on Oliver’s first day as one of six Resident Clerks on the top floor of the Foreign Office building from where all out-of-hours Foreign Office business was taken care of, albeit it in quite an unorthodox manner. ‘Often when the phone rang,’ writes Julia, ‘the duty clerk would be on the loo, or in the bath, in the big, bathroom papered in dark green. He would emerge, receiver clasped under chin, wire stretched to the limit and towel draped strategically, gesturing urgently for a notebook and pencil’. After a brief time on the job and after many gallons of Mateus Rose, Oliver is posted to Aden. Two years later, the couple marry on a freezing February day and it doesn’t take long for Julia to realise that one of her biggest challenges in her new role as diplomatic wife was going to involve creatively trying to keep herself busy whether at home or abroad. Nonplussed and with no immediate posting for Oliver in view, Julia dives into her new role and joins a ‘Going Abroad Course’ for five days of ‘pep talk, stiff-upper-lip training, a demonstration of the latest fashion in spycraft and a spoof ‘Cocktail Party’’. She attends a meeting at ‘Diplomatic Neighbours’, an organisation that supports and entertains the wives of foreign diplomats in London as well as others offered by the ‘Diplomatic Service Wives Association’, ‘a support group of volunteer wives with a rather genteel approach that was established by the FCO on welfare grounds, after a wife had committed suicide abroad’. Discouraged by the FCO from seeking employment, Julia goes ahead and finds one anyway. However, after two years of married life and in the very same week that she qualifies as a full social worker, Oliver is posted. The year is 1970 and the couple set off on their first assignment together to Cyprus – a place Julia describes as ‘a sanctuary and sometimes a terrorist convenience’ and where later she is visited by George Best and Derek Dougan among a string of many other high profile names. ‘The Ambassador’s wife’s Tale’ is Julia Miles’s account of her time following her husband’s diplomatic career from one posting to another and adjusting to the trials and tribulations that accompanied each and every one. Although women’s role in the diplomatic service shows a positive –if rather slow – improvement, Julia – always amused at the public perception of the diplomatic lifestyle – paints a picture that tells of the limitations and highly demanding expectations placed on the wives of the heads of missions by the patriarchal FCO as well as highlighting the extremely vital role that a diplomatic wife plays in a diplomat’s life; a rather under-appreciated, unpaid, behind-the-scenes role. The couple has lived in Cyprus, Saudi Arabia, Athens, Libya, Belfast and Luxembourg and so it comes as no surprise that Julia has a treasure trove of stories to share. From near disastrous dinner parties, to dining in the most elegant of settings with the rich and famous as well as members from Royal families and world renowned political figures, you can rest assured that Julia’s observant eye for detail would have missed nothing. A determined woman who, spurred by a feminist confidence to assert her rights and that of other diplomatic wives, she is cowered by no one, preferring –against better judgment at times - to wear her heart on her sleeve and in turn to write openly about the conditions of diplomatic wives and the often challenging circumstances she, and others like her, have had to put up and make do with. Throughout her memoir, Julia raises various criticisms particularly directed at the FCO’s treatment and disregard for the diplomatic wives’ concerns. In one example she writes: ‘The Foreign Office loftily exploited the diplomatic wives’ good nature and any complaint to the Diplomatic Service Wives Association was met with, ‘It’s for the love of your husband’’. Julia went on to have 4 children (two Cypriots, one Saudi and one Greek she would joke) and even that brought no respite from burgeoning diplomatic duties. ‘We were expected to entertain as much as possible, limited only by our entertainment allowance and the amount of energy and commitment that I, as cook and hostess, could summon up’. Matters were not helped when a remit by Heath in 1970 was to look at ways to cut government spending resulted in the government’s decision to cut the British diplomatic service finances by at least 1% every year, gradually eroding services. This proved particularly difficult for the couple’s posting in Saudi Arabia which did not help an already challenging post in a country that seemed not only to have an especially virulent effect on personal relationships but there were signs of depression and stress among the secretarial staff too. For Julia, it was the only place that tested the limits of how much more she could take before she threw in the towel. Luckily, she persevered. Although the couple only spent a year in Saudi Arabia, Julia’s account of her time there is colourful. With it being nearly impossible to obtain a visitor’s visa to the Kingdom, Julia was homesick and finding the post quite challenging. Although Saudi was the world’s honeypot in 1976, she was incensed by the country’s restrictions on women’s freedoms. She writes about Princess Saud who ‘like most Saudi women her spirit had been extinguished long ago by the system’, finding a toothbrush in her Coco Cola bottle, and starting soirées at the embassy ‘deliberately trying to widen Saudi women’s horizons’; gatherings that inadvertently helped her husband establish valuable connections with the Saudi men waiting in the kitchen to collect their womenfolk. She writes of the censorship exercised against freedom of the press, limited water, flour and oil supplies and ‘stakes a claim to having first introduced the pineapple into Saudi Arabia’. She also writes her account of the circumstances surrounding the death of Princess Misha’al, the great niece of King Abdul Aziz – the founder of modern Saudi Arabia. Parties and ‘whinging’ aside, the exciting – if not terrifying – part of the book is Julia’s account of the events that take place in Libya – Oliver’s first posting as Ambassador – that resulted from the shooting of PC Yvonne Fletcher outside the Libyan Embassy in London on 17 April 1984. The embassy – with Julia and her children still inside - is placed under a nine-day siege and then when it looks like Prime Minister Thatcher is about to break all relations with the country following a bomb (presumed to be Libyan) at Heathrow, it becomes a ‘cloak and dagger behaviour to get things sold and out of the embassy in time’ before the evacuation of Libya. Although a stressful time by all accounts, Mrs. Miles comes out trumps and it is her stoicism and admirable quality of ‘making-do’ that see her and the other British families through the stressful ordeal. ‘An Ambassador’s Wife’s Tale’ is a very engaging read. It offers a glimpse into an often glamourised world associated with characters as in an Ian Fleming novel. Yet, as Julia proves, at the heart of these missions are ‘individual diplomatic personnel, traditionally accorded respect and deference by the host country, often becoming pawns in international squabbles – in the worst cases as victims of kidnapping or even assassination. Diplomats’ children flying unaccompanied between post and school become a source of anxiety for mothers waving them off from foreign airports’ and always the knowledge that so much time is lost away from loved ones while in ‘vassalage to the Foreign Office’. Julia succeeds from the start in building enough tension into the narrative so that her readers will be turning pages to find out what happens next. The heart of the book – its climax even- lies in the Libya siege – the event that was to thrust Julia into the spotlight. By the time you’re done with this inspiring, bitter-free, entertaining memoir, you’ll understand why after 28 years of being an Ambassador’s wife, and finally ‘having her own front door’, it was time for Julia to tell her story and why the world would do well to listen.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed