|

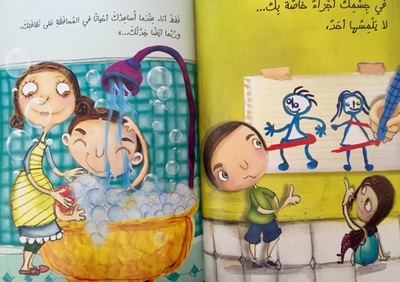

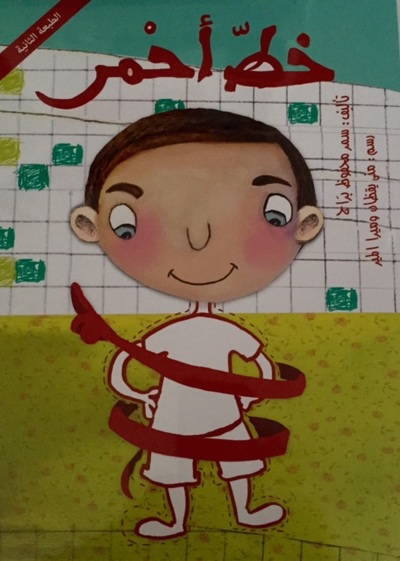

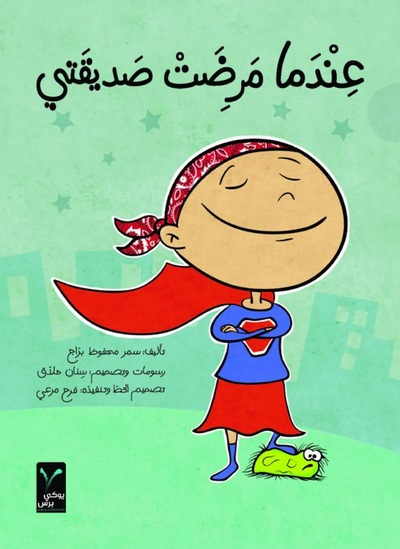

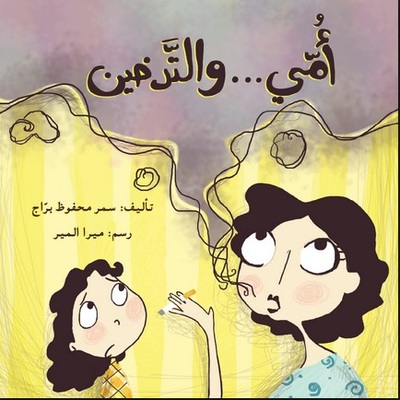

by Rana Asfour Last month, at one of the sessions at the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, a female member of the audience commented that she felt the time was ripe for writers to overcome archaic ‘taboo’ issues where children’s literature was concerned. The move, she stressed, was imperative if authors were ever going to grab the attention of the contemporary, globally aware, young, Middle Eastern reader. What happens next is remarkable. As soon as this soft-spoken woman introduces herself and offers the name of her book as an example on overriding taboos, the female guest speaker, now recognising who the author is, gets up, hugs her, congratulates and thanks her for a ‘magnificent piece of work’. The woman is children’s author Samar Mahfouz Barraj and the book is ‘Red Line’, one of the author's 45 children’s books to date. Session over, I make my way to the petite, stylish, charismatic author and introduce myself. I am delighted when she agrees to meet with me the next day for a chat. And this is how it happened that I found myself engaged in a delightful conversation with this Lebanese author about her work, the huge responsibility that comes with writing for children and the reason why she thinks her books have garnered attention and amassed a following of young readers and their parents. ‘Maybe it's because I like to write books that are both serious yet humorous’, this mother of two grown up daughters tells me, ‘I know that the subjects I write about can be considered delicate or sensitive by some readers, but they are subjects that must be talked about nonetheless. I believe that there is nothing that you cannot write about when it comes to children’s books, but it depends on the format that these topics are presented. We should stop hiding behind taboos’. One of Barraj’s books, shortlisted for the 2011 Etisalat Award at Sharjah International Book Fair, is ‘When My Friend Got Sick’ which won the second prize for children’s books at the 2011 Beirut International Book Fair and the Arab Thought Foundation’s Kitabi award in 2013. The book introduces the subject of cancer to a very young audience. Understandably, she was a bit apprehensive on how it would be received by the public. ‘I totally believed in my product yet I was so conscious of societal sensitivities that I refused to run it by any of my students or even young readers until after it went into print. Yet, when the book came out, the reaction of the public was very positive. Which goes to show that publishers who exaggerate their over-protective attitude to what children should/shouldn’t read or are reluctant to rock the boat, can sometimes hinder the production of books that can be a valuable resource to children’s education’. In 2014 publishing house Dar Al Saqi took a chance on Samar Barraj’s book ‘Red Line’ dubbed as the first children’s book, in Arabic, to broach the highly sensitive subject of sexual harassment. Extensive research was carried out by Barraj (involving psychologists and child professionals) and after a rigorous round of writing and re-writing and closely working with the illustrators, ‘Red Line’ hit the shelves and was met with resounding, overnight success. As it happened Barraj had brought a copy and proceeds to read me the story. I listen, quite self-consciously at first, until I am no longer anything but caught up in her narration, her tone, the vivid pictures on the page. The book, I swear, is alive. When she’s done, she smiles. It’s like she knows her magical storytelling techniques have worked. I’m hooked; lock stock and barrel. When she’s done and I find the words, I ask how people reacted to the book when it came out. ‘I was amazed and very pleased by everyone’s reaction to this book. I wrote it because I believe it helps to educate the child in a simple way and at the same time without the intimidation, fear and shame usually associated with a serious subject such as this one. I relied on a humorous storyline, great illustrations, and wrote with educators, parents and children in mind. I have had great feedback and it turns out people wanted to talk about harassment with their children but didn’t know how or where to start and I have been told that my book has provided them with a great starting point’. ‘Although hesitant at first, schools are soon eager to bring the book into the classroom once they read its content. As a teacher, I fully understand the role of the school and believe that it should be the medium between the children, the parents and books that are of value. That is why it was important for me that schools get on board with ‘Red Line’. The objective of the book is that it helps raise children’s awareness on the subject of sexual harassment and it gives them the courage not only to deal with this situation, if it arises, but to talk about it without shame with an adult they trust. We need to educate children that some 'bad' things are out there and we need to give them the tools so they are strong enough to deal with anything in life'. Barraj began her career as a teacher after completing a BA and teaching diploma at the American University of Beirut. She went on teach for several years, which has served to fuel a passion for writing her own children’s books. She now boasts a collection of 45 published titles, has presented several training workshops and participated in various activities to promote reading among children. She is a member of the Lebanese Board on Books for Young People (LBBY).

‘I want children to pick up a book and read it mainly for the purpose of enjoyment. The workshops that accompany many of my books rely on performances and puppetry, all in the aim of demonstrating that reading can and must be primarily about creativity and fun. Our children only read books that are part of the school curriculum and that is not the same as reading for pleasure which is done away from the school environment’. Much of Barraj’s life experiences have trickled into her work. By her own admission, this is quite unavoidable for any author. Her book ‘My Grandmother Will Always Remember Me’, that won first prize for Children’s books at the 2012 Beirut International Book Fair and was translated into Spanish, is based on her childhood memories growing up with her grandparents, ‘By the Light of the Candle’ was inspired by conditions she lived through during the Lebanese Civil War and is ultimately a story about peace. Her brother proved to be the inspiration she needed for her latest book ‘Ma Ahla Alnaoum’, nominated for the IBBY honour list 2014. ‘I do go back to my experiences and draw inspiration for my stories. For example, I grew up with my grandparents and now as an adult I realise how not only is it the duty of the young to care for the elderly in the family but it is also about the grandparents showing an interest in their grandchildren in order to bridge the gap between the generations. Reading to and with children is one way of achieving that’. As if anticipating my next question on whether that means her books carry messages, Barraj is one step ahead of me and continues that ‘because the common notion is that children’s books must carry some educational message, it should be in a way that does not spoon-feed audiences or hinder creativity. Freedom and space should be allowed readers in order that they may draw their own conclusions regarding what they think and how they will deal with the world around them. My main job as a writer is tell a good story’. Two years ago Barraj embarked on a pioneering collaboration with author Fatima Sharafeddine that resulted in the young adult novel, ‘Ghadi & Rawan’. The story is about two teenage friends who try to maintain a long distance relationship while trying to overcome the difficulties of being in two separate countries, not knowing whether they will meet again. ‘As co-author of this book, it was my job to pen the voice of Rawan, the Lebanese girl who stays behind and it was only natural that Fatima should write the story of Ghadi as she herself lives between Belgium and Lebanon. It was a very exciting and fresh experience but it was also a challenging one. This is a story between a teenage boy and a teenage girl after all, and in the Arab World that doesn’t come without its own set of issues but it worked and we were able to produce a format this is engaging and modern’. In spite of the success her books have received, Barraj concedes that there is a real problem getting this generation to read and when they do, it is not Arabic books that they choose. This she attributes to a literacy problem. ‘I write in Arabic to encourage people to read in a language that I love. I have noticed that children nowadays like listening to Arabic stories but have a hard time reading them for themselves. The Arabic language curriculum is suffering and as a result children’s command of the Arabic language is not as strong as it should be’. Quickly the times passes as Barraj reads to me one more of her stories about a whale called Tooti and another about a ‘magic card’ whose graphics my almost-into-his-teens son will just love. After I say my goodbyes and step back into the real world, it dawns on me that we all love stories. And you know what? Storytellers are the really lucky ones because they get to tell them all the time and that’s a pretty cool job if you ask me.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed