|

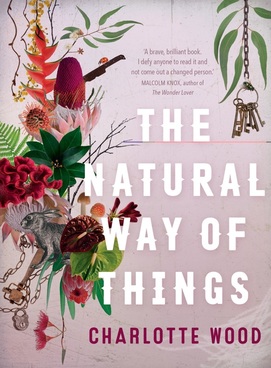

by Rana Asfour Winner of the Stella Prize and the Best Fiction and Overall Book of the Year at the Independent Bookseller Awards - Shortlisted for the Victorian Premier's Literary Award - Longlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award Two women, Verla and Yolanda, strangers to each other, wake up in a strange place, in clothes not their own with no knowledge of how or why or who has done this to them. It is clear to both of them that they have been abducted and as they slowly resurface from their drugged state are able to discern that they are being held in some kind of abandoned farm.

And they are not alone. They are soon to join eight other girls who have suffered the same fate. Of varying ages, these women who are quickly able to identify each other realise they have one thing in common: they have all been involved in a public sexual scandal of one kind or other in the outside world and have told about it. It is Summer and the place, somewhere in the Australian outback, is suffocating with its heat. Locked up in unaired 'dogboxes', with heads shaved, the girls suffer the sweltering heat by being forced to wear a stiff long green canvas smock, a coarse calico blouse beneath, hard brown leather boots and long woollen socks and ancient underwear. They are forced into back breaking manual labour, denied all basic forms of hygiene. The ten prisoners are under the guard of two abrasive, cruel and 'pathetic' men, Boncer and Teddy and the repulsive, slightly mad, make-shift nurse, Nancy. The theme for the story, although sounds surreal is actually inspired by something the author had once read about. In an interview with the Stella Prize Award, Charlotte Wood had this to say: 'I heard a radio documentary about the Hay Institution for Girls, a brutal prison in rural New South Wales (NSW), where ten teenage girls were drugged and taken from the Parramatta Girls’ Home in the 1960s. One of the reasons many of the girls were in the Parramatta and Hay homes was that they had been sexually assaulted – at home, or wherever, and had told someone about it. It was this – speaking about what had happened to them – that got many of them sent there. They were deemed to be promiscuous and ‘in moral danger’. This seemed to me to be the worst thing: that their ‘crime’ was that they had spoken up about being abused'. She adds: 'I began noticing that this punishing attitude was not something belonging only to the past, because things kept happening in the contemporary world around me that showed those views were not historical. The punishment of women for being sexual, and for speaking up, happens all the time. I started imagining some girls who find themselves in this remote place as punishment for some kind of sexual scandal with a powerful man'. This is not a quick read or an easy one or a comfortable one at all. Although mired in modern realism this is a novel that holds up a terrifying present in which women are blamed for the violence that happens to them, and one in which unless a woman conforms to what society in general, aided by the media, define 'femaleness' to be then she is to face being 'disappeared'. The novel's setting is grim and the reading experience creates a sense of claustrophobic isolation. Although devoid of hardly any graphic violence it is nonetheless one of the most violently sexual books out there at the moment. And then there is the novel's underlying anger, unvocalised perhaps, but there all along, just as there remains the conscious awareness of a fully charged electric fence surrounding 'the compound'. And although with the seasons dragging on, the prisoners stop hearing the low hum the electricity creates as it courses through the wires, it doesn't mean that it's not there. It is as if the writer wants you to remember that, even through the briefest displays of kindness and small victories, the anger must remain with nothing allowed to deter from the cruelty and injustice of the prisoners' situation. Anger is defiance and ultimately when we see all emotions squashed one after the other, anger becomes the prisoners' and readers' only hope! That said, there is - surprisingly - tremendous beauty and empowerment in the book; beauty in the language and in the descriptions of the natural surroundings of the prison grounds. And when a justice of sorts finally comes in the end, there is a twisted sense of unsatisfied violence, further proof of how savage and revolting a pacifist such as myself - a human - can be.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed